| |

| The Photographic Diary of Corinne Day |

| The photographic Diary of Corinne Day: An extensive study on her visual practice with reference to Laura Marks and Nan Goldin. |

The Dark Room

The Observer Magazine 6th of January 2002

By Sheryl Garratt |

| In regards to a recent exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Sheryl Garratt for the Observer interviewed the widely acknowledged and celebrated photographer Nan Goldin. For over thirty years now, Nan Goldin documents the life of her friends and the relationships she shares with them. Inevitably that also means that she documents her own life. In sometimes very intimate images she proved that a camera could record physical but also emotional bareness. Confronted with her work, the viewer realises that these personal extracts of life are in a broader sense the truth of relationships we have with others and ourselves. |

| Growing up as the youngest of four children, Nan Goldin (born 1953 in Maryland) unexpectedly became closest to the eldest of her siblings. When she was eleven years old her 18-year-old sister Barbara committed suicide. Without a doubt, this incident had a life long effect on her, even though Nan knew it was going to happen since her sister told her years before. An upcoming installation in her new hometown of Paris is supposed to be about her sister’s death and mental illness. The obsessive need to record memories and her particular interest in women’s sexuality are also symptoms instigated by her sister’s death. |

| After being kicked out of school and running away from home she ended up in a commune with the age of 14. Through a friend she discovered photography as a tool of communication and started to explore Boston’s gay scene. Another turning point in Nan Goldin’s life was at 18 when she started to photograph what she calls the third gender. Her photography become more sophisticated with her series on drag queens - parallel to that she also started to use Heroin. After living in London for five months she moved back to New York where she exhibited her work in underground venues as slide shows. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency originates from that time period and is until today her most famous body of work. |

| The photographs, and in particular her self-portraits, are proof to very rough periods in her life full of drugs and violence but also love and compassion. In one incident her boyfriend battered her so badly that not only she almost lost her eyesight, but even might have lost her life. After years of self-destruction she finally went into rehab where she wanted to turn her back to drugs and where she was forced to turn her back to photography. After rehab Nan Goldin started a more settled life style by moving into a halfway house and neglecting the myth that the source of inspiration is found in drugs. |

| It was in this time of self-reflection that she started to learn about natural light and its effects in her documentary style imagery. Having that in mind the scenes she photographed also changed. The photographs of underground clubs, run down hotel rooms and squatting communes tended to be introverted, even claustrophobic. Her more recent works are photographs of her friends bathed in sunlight in places such as the Riviera or Sicily. Nan Goldin’s concern is also how the camera effects her immediate environment, whereas the ambiguity of the camera certainly adds to the complexity of her relationships. |

| Along with a subtle change of photographic style, her tribe or family as one might want to call it, also transformed. A lot of the people she photographed in the 70’s and eighties died of AIDS - the virus was discovered only a few years after she got off Heroin in 1973. Nearly every drag queen Nan Goldin ever lived with died and many faces of The Ballad also vanished. Ironically her newest slideshow is called Heartbeat and it features a more positive take on life. Babies and children presented in this piece are symbols of renewal, whereas she rules out that there is any deeper meaning to it. In either case, Nan Goldin has gone full cycle by sharing stories of life, death, love, hate, illness and happiness – and she leaves it up to us to see and reason. |

The Skin of the Film

Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses

By Laura U. Marks |

| In her book The Skin of the Film, Laura Marks states that the roots of what she calls intercultural cinema lie in the immigration to Western metropolitan centres. The artists within this movement are minorities that produce their work in the cultural apartheid of a predominantly white Euro-American West. Intercultural films deal with the exile and displacement of many different minorities and therefore also draw from different cultural traditions and memories. The experience of Diaspora (in this case not only referring to a Jewish but to a general phenomenon of exile) expressed in film and video has lead artists to use various ‘languages’ that represent their world. |

| Laura Marks argues that the cultural differences mixed with individual memories perpetuated on film, appeal to non-visual senses such as touch, smell and taste. She extends this argument in saying that certain imagery appeals to a haptic visuality that invites the viewer to respond in an intimate, embodied way. Film and video in general, and for that reason not only intercultural cinema, can represent non-visual sense experiences that can also be combined. |

| The increase of multicultural debates, the availability of governmental funding and the disintegration of minorities meant that the movement of intercultural cinema was its strongest from 1985 to 1995. The general popularity of what then became a genre also had the consequence that a lot of films fell into he grey area of commercial and non-commercial. Artists from a visual minority were sometimes supported because of a multicultural policy in the public fund. However, since governmental subsidies for art declines, it becomes more difficult especially for artists of colour to get supported. |

| With a lot of filmmakers turning to other private investors, their works changed from exploring their cultural homelessness to the commercialisation of multiculturalism. Nevertheless, many films continue to be produced that contemplate on the emptiness of displacement and disintegration. In rediscovering his/her own past the filmmaker is sometimes forced to deconstruct the dominant history in order to create space for stories of intimacy and proximity. Such films sustain with very little words (short films are often preferred to the feature length), and parallel to that they are emotionally rich. |

| The term ‘intercultural cinema’ implies that there is a dynamic relationship between the host and the minority culture. The genre emphasizes on the cultural differences that continuously transform a nation from within, leaving it open for discussion if terms such as ‘fixed cultural identity’ are possibly outdated. This shows that cultural Diaspora is both, productive and deconstructive. It forces cultural minorities to question issues of heritage and identity, but it also led them to express their ideas which can only be understood as an asset to society. |

| In doing so the individual searches for a language to express their cultural memory that inevitably leads to absence. By digging out old photographs and film footage (artefacts of culture that are usually held on to) the artist will soon realise that cultural memory is in the gaps of such imagery. The suspicion that conventional imagery cannot hold whatever the individual artist interprets as cultural memory led them to what Marks calls “new forms of expression” (Marks, p. 21). |

| This form of expression also involves senses other than seeing and hearing. In order to evoke a cultural knowledge the filmmaker might appeal to our sense of touch to embody a memory that cannot be seen but only felt. Therefore if vision can understood to be embodied, Marks argues “other senses necessarily play a part in vision.” (p. 22) A film engages with our own memory by stipulating all senses in the viewing experience. The new form of expression is that non-visual cultural experiences can be represented with a haptic visuality that can be learned and cultivated. |

| Introduction |

| In regards to a body of work that challenges dominant cultural theory, I would like to discuss Corinne Day’s photography. She only recently gained recognition as a documentary photographer with the publication of her book called Diary in 2000. Over a period of nearly a decade she captured her friends lives, in what turned out to be an extensive project containing over one hundred images. By viewing her book, one soon realizes that Corinne Day’s work is strikingly analogous to that of Larry Clark and in particular Nan Goldin. In addition to that, the biography of Day and Goldin also read alike which inevitably leads to the question if similar experiences lead to similar forms of expression. |

| Their lifestyle on the edge of existence has transformed their immediate environment into minority groups that struggle with their identity and their placement within society. In a broader sense, Day and Goldin’s squatting, drug taking and hospitalising experiences are cultural differences most others do not share with them. In a dramatic directness, both photographers have recorded these experiences, ignoring most barriers of political correctness. As Laura Marks argues in The Skin of the Film (and certainly this is also applicable to photography), these images of individual memories mixed with their cultural difference appeal to a ‘haptic visuality’. It is open for discussion if imagery such as Day’s or Goldin’s is more likely to deliver a viewing experience that leads to an embodied response with other, non-visual senses involved. |

|

Nan Goldin, self-portrait, 1999 |

|

| Picture Analysis |

| In order to fully comprehend how Day’s photography challenges the viewer and society, it is important to analyse her work as single images, but furthermore also as a book format. The title Diary is self-explanatory in regards to the very personal and intimate pictures of friends and herself. As Michael Bracewell writes for Creative Camera, a dairy is “a simple juxtaposition of an individual and their circumstances” (CC, No. 351, p. 20). However, Corinne Day’s Dairy is more than that, it is the “juxtaposition of personal and generational trauma” (p. 20). |

| As oppose to chronological entries into a diary, Day chose to produce a body of work that reads like a poem rather than a strict enumeration of experiences. For that reason it is almost impossible to chose a key image because they all read as one piece. One of the greatest accomplishments proven in Diary is the editing and sequencing by Michael Mack. Diary truly reads like a book with several chapters with a proper beginning and an end. Every single image finds its proper place to a story that came before or after it. For that reason, not only images across from each other but also back to back relate and intensify their meaning. |

Tara at home Stokenewington squat 1998 |

|

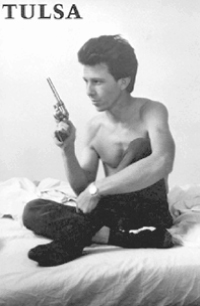

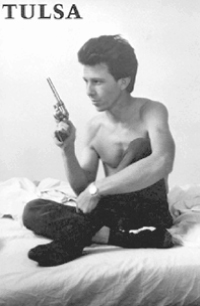

Book cover of Tulsa, 1971 |

|

| On the book cover we see the face of a girl with Ketamin snot up her nose. Right from the beginning on the pace is set for the pages to follow. Later, the viewer finds out that Tara - a single mom from North London - is the main figure in Diary. It is mostly her who tells stories of poverty, drugs and unfulfilled dreams. In one image we see pregnant Tara looking at her belly through a mirror. The viewer can hardly identify her since the backlight from a window reveals only her silhouette. It is only in the mirrors reflection that we can see her bruised and tattooed body. As a single image it might be interpreted as one of happiness since new life was created. But within the context of the book it is an image that is troublesome and makes the viewer worry for the child’s health. |

| It is a similar image in Larry Clark’s Tulsa that puts a friend into the same context of ambiguity. In an almost pictorialist fashion Clark photographed a pregnant woman sitting on a chair in front of a window. The optimism is soon to be destroyed with a photograph of a three-foot coffin. With out a doubt it is the coffin for the newborn of Clark’s friend who was a notorious heroin shooter. In Diary though, the take on life and birth of life is different. The viewer identifies Tara as an inopportune individual who is forced to live a life at the edge of society. Nevertheless, she also seems to be a loving and caring mother in pictures where she bathes or feeds her baby. |

| Another very powerful form of expression in Diary is the layout of the diptych. Here the editor chose to juxtapose images that relate to each other, either literally or visually. For example we see an image of a giant size gun across to a photograph of someone shooting up. The needle and the gun point into the same direction, but furthermore on the page spread it seems as if they are an extension of each other. It almost seems as if Day wants to say that one inevitably leads to the other. The gun as well is a reminder of days in Tulsa. In another very blunt exemplar of a diptych, there is a house that has been blown down opposite to a friend lying stoned on the ground with her eyes half open. The tones of the sky melodramatically repeated in the blue tapestry in Tara’s apartment. |

| One of the most striking combinations of photographs is almost exactly at the end of the book. By then the viewer assumes to know what Tara’s, Corinne’s and their friends’ life is all about. But where does it go from there? At first sight a photograph of a leafless tree that caught some cellophane in the wind only adds confusion rather than resolving any questions. Next to that it is Tara in a hospital. The shape, colour and texture of the swirling cellophane is gently repeated with the bandage she happily takes of her hand. |

Tree and cellophane Soho 1992 |

|

Tara in hospital 1999 Tara in hospital 1999 |

|

| Her smile changes the whole mood of a winter night photograph showing a skeleton like tree. The trees leaves are going to grow and overshadow the garbage it was caught up with. As much as spring leaves winter behind, the viewer hopes that Tara leaves the hospital and therefore also her self-destructive lifestyle behind. The following and also last photograph of a trashed beach shows that bliss does exist, but it would take time to heal the wounds of the past. |

| Source Analysis |

Obviously my major source is the work Corinne Day is best known for. However, Diary can only be looked at as a visual source that leaves a lot of space for interpretation. The only coherent sentence written in the whole book is following one: |

Good friends make you face the truth

about yourself and you do the same for

them, as painful, or as pleasurable, as

the truth may be.

for Tara |

| In many ways these words are the essence of Diary. It shows that although Tara is the main figure Diary is as much a portrait of Corinne Day. In some cases these are portraits the artist was comfortable with. In others she shows apprehensiveness towards her own image – referring to both, a photograph and a character projected to the public. In photographs from hospital before and after a brain tumour was removed she refers to herself as ‘me’. In pictures where she is smoking up or is stoned the caption reads ‘Corinne’. It is the painful truth, she refers to in the sentence above, that she made herself and others face. It seems as if the “visual diary is about the photographer’s desire to sabotage her own identity” (CC, No. 351, p. 20). |

| Another source were the numerous photo shoots and articles dating back when she was renown for her photography contributions to The Face, Ray Gun, Vogue or even Penthouse. In a page spread for the June 1993 issue of Vogue she photographed then unknown Kate Moss – a friendship that dates back to Day’s six-year modelling carrier. The photographs show the model very sparsely dressed in what seems to be a boring day at home. The images were so controversial that the New York Times was even “suggesting possible child pornography” (BJP, No. 140, p. 17). Plausibly, these comments actually boosted Moss’ and Day’s carrier instead of doing the opposite. |

| The rather prude British Journal of Photography wittingly or unwittingly predicted Day’s massive ascendancies in photography. In an article published a month after the legendary Vogue spread they write: “It is important, however, not to lose sight of Day’s work. The essence of reality her images hold reflects the time and friendship she puts into each shoot.” (p. 17). By stating the restrictions of the magazine format and the obvious advantages of the book format, Day herself makes a substantial prediction in that same article. |

| Interestingly enough, seven years later it is again the British Journal of Photography that runs a comment with the title “Crisis is genuine and widespread” (BJP, No. 7304, p. 3) in reference to Diary that was exhibited in The Photographers’ Gallery that year. It is said that Day’s photographs caused a crisis in documentary photography by confronting the viewer with images such of “menstruation-bloodied knickers, three explicit images of drug use and a dog pulling at the hair of a doll.” (p. 3) The Journal goes on by declaring, “that Day’s drug taking images glamorise their subjects given the context.” (p. 3) |

| In a book called Imperfect Beauty a few photographs from Diary were also published. Along with other peoples fashion photography is an essay Day wrote herself. In it she describes how she met all the people who ended up in Diary, which led to odd sentences such as these: “I met Susie through Pusherman – Susie used to go out with Andy. Susie and I worked together.” (Cotton, p. 60) Nonetheless, the essay expressed very clearly how these people and others influenced her visual practice. Besides bringing up Larry Clark she also mentions the purchase of Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Independency as a major liberation for her own photography. |

| Influences and Methodology |

| By reading Nan Goldin’s and Corinne Day’s biographies one realises very soon that their lives have been similarly accompanied by poverty, drugs and friendships that are comparable to family - probably because of these circumstances. The main difference is that Goldin’s photographs are of sexual identity whereas Day’s work is more likely about the identity of a whole class. Nevertheless, both Goldin and Day lived their lives in this class that is marginalized and usually behind closed doors. |

| With sixteen years of age, Day was only two years older than Goldin when she left school. Their family history is similarly convoluted whereas Day moved to her Grandmother - who is also included in Diary - when she was five. This might have to do with the fact that her father was, as she herself says, a “professional bank robber” (Cotton, p. 60). The questionable relationship with her parents is also depicted in her book with a picture of family members darkened down to an extent that the viewer can only identify Tara. |

| Day’s introduction to the model scene and Goldin’s experiences in gay and drag queen subculture lead to drug habits that were shared with friends and fellow users. It was also a lifestyle in squats, claustrophobic apartments in ever changing localities. The list of cities Diary was shot in (London, New York etc.) reads almost exactly the same to places where Goldin also lived major parts of her life. Apart from their background, Day and Goldin share the love for blunt directness with photographs of sexual intercourse or remains of violence. Clearly, these images have been a challenge to a society that tries not to acknowledge the existence of people on the far end of it. |

| The paradox is, although Day’s work is so highly controversial and unaccepted by a large population, it is parallel to that very successful in delivering a paradigm. Day’s ‘Dirty Realism’, also comparable to Richard Billingham’s or Boris Mikhailov’s work, is highly successful in presenting us stories that can only be written by life itself. By “discarding any aesthetic or journalistic safety net” (BJP, No. 7299, p.25) she is aware of the risk that Diary bears, and more importantly produces images that leave little space for interpretation apart from pure reality. That this reality is dirty, or intense as others call it, is less a matter of a photographic style – it is a way of life the image-maker chose to live long before even thinking of recording it. Without praise, it is this particular lifestyle that can be accredited for Day’s, and of course also Goldin’s body of work. |

| Not only the subject matter but also their approach to photography is very similar. With having no formal education in photography, their imagery is spontaneous, unconventional and challenging. Both prefer the small format since its more flexible and allows more freedom whilst shooting. Technically Day and Goldin aren’t always on top of things, which in many cases add to the strength of the image. Some parts can be severely underexposed, blurred or out of focus. Because both of them tend to shoot indoors they use pretty fast films that makes the prints grainy and full of contrast. Mixed light conditions also mean that in some cases the pictures come out red, green or yellow. All these are attributes that might lean towards a literal understanding of ‘Dirty Realism’. |

|

Richard Billingham, 1995 |

|

|

Boris Mikhailov, 1999 |

|

| Since their background and their photographic style is strikingly similar the question appears if there is a commonality in personal history and forms of expression. Photography for Day and Goldin certainly was a way of dealing with their lives at times when its future was unpredictable. It gave them the chance to reflect on their lives as much it is sometimes helpful to write about it. It is no news that the camera can have therapeutic effects especially on someone who struggles with memories of loss. In Goldin’s case that certainly was the death of her eldest sister. In Day’s case that is a general love for nostalgia that led her to regret periods in her life that “have gone unphotographed” (BJP, No. 140, p. 16). |

| Conclusion |

| Weather it is based on the love for nostalgia or a general consensus with loss and ultimately death, Day’s realism has invited the viewer to do much more than just to look. The very intimate photographs of her friends and herself are an homage to life, despite all its life derogating depictions. It is Day’s reality of living that enables the viewer to respond to her photographs almost as if they are windows into an unknown world. As much as some of us might be appalled, the invitation is honest and genuine. One has to ask himself if it is more appalling to know that someone photographs reality, than it is to know that this reality indeed exists. In effect, Day has broken a pattern that put up a mirror in three directions: her friends, her self and the viewer. |

| The most challenging aspect of Day’s work is that the viewer commences to identify with people from assumingly a lower class and a lower acceptance. We recognize aspects of humanity that go across any definition of class: happiness, depression, love, hate, existence and absence. These intimate moments Day has captured lead the viewer to respond to them much differently then to a conventional photograph from a magazine or catalogue. Indeed this phenomenon can be called ‘haptic visuality’ as Laura Marks describes it. In the photograph of pregnant Tara standing naked in front of a mirror, Day has managed to dig into the deepest layers of human instincts. If man or woman, the viewer cannot help but develop a motherly instinct and feel goodwill for the expected baby. |

|

Canned beach 1994 |

|

| This embodied respond to an image can lead to tears, laughter, aggression and shame. Certainly, this cannot fully be accredited to Corinne Day, but more likely to the subject matter she chose to photograph. It shows that the realism in Day’s photographs is as much a necessity as it is an efficiency that invites the viewer to look through that window in order to feel and hopefully also to understand. |

Marco Bohr, 2002 |

| References |

• Horsburgh, Lesley. Seize the Day. British Journal of Photography, No. 140, July 8 1993.

• Corinne Day: Diary. British Journal of Photography, No. 7299, Oct. 25 2000.

• Crisis is genuine and widespread. British Journal of Photography, No. 7304, Nov. 29 2000.

• Bracewell, Michael. Corinne Day: Diary. Creative Camera, No. 351, Apr/May 1998.

• Cotton, Charlotte. Imperfect Beauty. London: V&A Publications, 2000.

• Charlesworth, JJ. Art Monthly, No. 247, June 2001.

• Marks, Laura. The Skin of the Film. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

• Garrat, Sheryl. The Dark Room. Observer Magazine, Jan 6 2001. |

back to essays |

|

| |

|

Tara in hospital 1999

Tara in hospital 1999