| |

| Book Review of Zoltan Jokay’s der, die, das |

Images and excerpts in this segment are taken from:

Jokay, Zoltan: der, die, das. Cologne: Schaden Verlag, 2001 |

| One of the most compelling bodies of work I recently discovered is that of Zoltan Jokay. Accompanying a large exhibition on the people of Ravensburg, Germany, he published a book with the title der, die, das (the translation of which doesn't do it justice). By photographing people in their immediate environment, he produced a sociological fingerprint of ‘small town Germany’. |

|

| On the very first page of the book is the photograph of an apple tree. Right from the beginning, Jokay sets the pace for what is to come. We all know about the connotations of the apple in the Garden of Eden. In my opinion, the artist is giving us a metaphor for youth and life rather than abandonment from paradise. The skeleton like branches of the tree and the grey autumn sky also suggest a general melancholy that follows us throughout the book. |

| The following image is that of a young girl standing in her driveway. It almost seems as if the leaves of the apple tree are leaping into the portrait of the girl, although many pages of introduction are in-between. The direct eye contact with the young woman is engaging and revealing at the same time. She doesn't seem to be happy, nor does she seem to be sad. It is the neutral expression on her face that keeps reappearing in Jokay's portrait of a small town. |

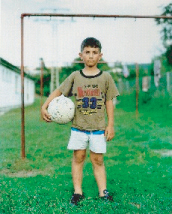

| Only a few of his figures are smiling shyly. His portraits of mostly children are frontal and convincingly objective. Although he might have directed the people photographed, Jokay seems to reveal who they really are. That can be accredited to the general trust children have - even in strangers. |

| I am implying that Jokay was a stranger to the subjects photographed in most cases. In his accompanying essay, Thomas Knubben writes: "Zoltan Jokay mostly photographs children. It is their proverbial openness that predestined them for the spontaneous meeting with the camera." |

|

| Certainly the photographer used this so-called openness for his own means. Towards the second half of the book, Jokay has included photographs of adults. The fact that a few of them are taken in interiors (kitchen, factory, hospital etc.) suggests that the artist had a closer relationship to the subject. In these cases Jokay probably wasn't dependent on a childish openness because friendships and family relations gave him already permission to photograph. |

| Evidently, the choice of portraits included in the book is part of a greater message. It is the "in Germany-born foreigner in him" (page 9) that led him to include to a large extent images of immigrants (Eastern European, Turkish etc.). In either case, all the portraits of Ravensburg share the fact that they were photographed with a very sensitive and sympathetic eye. In the foreword it says: "They are images of unusual proximity and partly irritating directness; simultaneously they are also images with a great amount of sympathy for the human being." |

| Along with all the sympathy for his subjects, Jokay also produced a self-portrait. Maybe it is what he sees in the person that reminds him of himself. This self-discovery process doesn't have to be present while Jokay is shooting on location. It can happen much later when the questions turn up of which images should be included or excluded. Clearly, the choice of images in the book der, die, das reveal a mysterious interpretation of childhood and also life in general that leads us back to the apple tree. |

In studying Jokay's work, the viewer discovers an omnipresent layer that suggests that the artist himself had a questionable childhood. This layer is a common thread throughout his portraits and reveals so much more than the faces of his subjects. |

| Nevertheless, it is my impression that Jokay might have carried his own personal conception of childhood a little too far. The children he photographed almost seem too serious. After all they are only children. In Claudio Hils accompanying essay it says: “In children’s faces we encounter the decisive expression of an adult, whereas adults seem to be lost in the world of the moment.” |

| The reason for this phenomena might be that Jokay photographed the children just like adults (frontal, eye to eye, sometimes monumental). It was the photographers’ choice to make them look like adults by using his creative means. This is not a valid criticism in itself rather than the discovery that der, die, das is more likely an artistic and not as much a documentary project. In either way, Jokay’s portraits have haunted me for quite some time now, which in this case speaks for the quality of his work. |

Marco Bohr, 2002 |

back to essays |

|

| |

| |