back to homepage |

|

| Essays on Twelve Photographs |

|

| Paul Caponigro, from the Woods series, Redding, Connecticut, 1968: |

| A few months ago I had the pleasure to attend a cocktail party held by a friend of the family. After I declared my interest in photography I was led into the hosts bedroom where I found to my greatest surprise an original Caponigro print. I saw the image many times before on badly reproduced slides or in various books. I almost didn’t recognize the original because it is actually a much darker print than its copies suggest. I was left alone for a few minutes to study the large fiber print. I realized that it projects harmony of repeating tones and purity due to the simple subjects photographed. The untouched nature is recorded in such a harmonic way that it could be visual homage to the place captured on film. |

| The subject as mundane it is, was documented with a very unusual approach. First of all the position of the camera on top of the water makes the viewer forget that in the process of photographing there is a camera involved. If Caponigro was standing in the water or on top of a bridge becomes irrelevant. The purity of the image leads us to ask far more metaphorical questions than technical ones. The camera becomes a tool of psychological exploration for the viewer and the image-maker. Caponigro describes his own technique as “soul searching” – an aspect which is clearly visible in the final print. The reflection of the trees in the soft looking water (caused by a long exposure) creates a rhythm reminding us of the beauty of nature and the photographer’s ability to use the medium as a form of self-expression and discovery at the same time. |

|

| Eugene Atget, Entrance to courtyard, cour du Dragon on the rue du Dragon, Paris 6, Paris, about 1912-13: |

| As Caponigro sees the beauty in nature, Atget sees the beauty in the nature of urban life. Endlessly walking around with a big cart with camera equipment, Atget produced thousands of documents on the city of Paris. He recognizes the repetition of forms and shapes and similarly to Caponigro concentrates on the importance of vanishing point and perspective. The results are images such as the ones from Versailles and documents of an ever-changing city - including the one on top. Atget showed in particular with architectural photographs a great amount of sensitivity for the detail. His images are well organized and structured. They appeal to our visual aesthetics because of an interesting range of focus, play with light and shadows, detail in texture and off-center framing. |

| Atget’s images of inner Paris also seem to reflect a concentration on one or in rare cases two vanishing points. His intention is to lead the viewer into the photograph in a very subtle way. The path our eye is supposed to follow is well thought of and prepared, facilitated by photographic technique and pre-visualization By concentrating on the streets of the city, Atget declares a great interest in the human condition, which stands in total contrast to Caponigro where mankind is detached from the image. Even Atget’s photographs from Versailles always emphasize the fact that men have altered nature. Atget’s images speak of our understanding of aesthetics and how this is reflected in our living, environment and beliefs. |

|

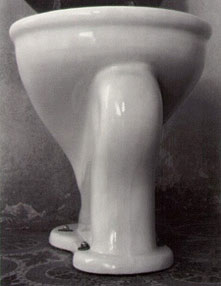

| Edward Weston, Excusado, Mexico, 1925: |

| Weston’s image of a toilet bowl was in many ways groundbreaking for its time and probably is one of the landmarks in the history of photography. Weston left the United States to distance himself from the art scene and its theories on photography. Pictorialism was widely practiced by Stieglitz and his company. Weston moved to Mexico for a new love but also to detach himself from a photographic approach he didn’t quite believe in. In these years of separation from the rest of the world he produced a remarkable body of work. |

| Excusado symbolizes fro me a new style, fresh inspiration but more importantly the belief in oneself. This belief directly influenced his style, which ultimately made his work so different from anything produced before. In Excusado Weston took a photograph of a ordinary object and turned it into a beautifully shaped organism. With the use of available light, an uncommon perspective and large depth of field, Weston overwhelms the viewer with texture and naturalistic characteristics in an industrially produced object. Excusado is an appeal to look at things in our domestic environment differently and change our opinion on the beauty where beauty is least expected. |

|

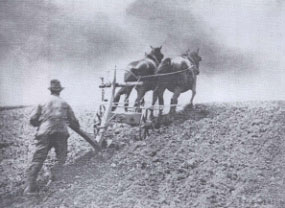

| Peter Henry Emerson, A Stiff Pull, East Anglia, England, 1880’s: |

| Peter Henry Emerson was a very well educated man when he started out to photograph. Among his interests was Helmholtz’s theory of optics, which states that our eye sees things sharp only in its center of vision. Emerson applied that to his photography by using a long focal length, short shutter speed and very narrow depth of field. His photographs are an application of physics in fine-art photography. The images were pictorial impressions of the English countryside and the common men. |

| The soft focus allows the viewer to concentrate on the center of attention without being distracted by its surroundings. This is a technique that is more than ever applied to portraiture, fashion and product photography. Fascinating about Emerson’s image is that he was also acknowledged as a documentary photographer besides being a scientist and artist. His photographs of the peasants, hunters and fishermen of East Anglia show a great interest in their way of living. It must have been strenuous to transport all the equipment to these remote places. To go through that struggle is also a sign of how the photographer identified with the struggle of these hard working but still poor people. Emerson presents them as heroes with low vantages points and sign of hard labor. |

|

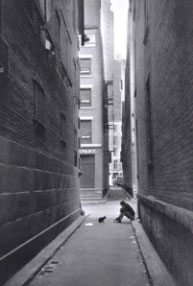

| Henry Cartier-Bresson, Near Wall Street, New York, 1947: |

| Henri Cartier-Bresson is probably my biggest influence in photography. By studying his work I adapted a similar understanding of composition and reaction to the moment. Just by observing the streets I would find ‘Cartier-Bresson moments’ and try to capture them in my own way. By mentioning the ‘moments’ I mean what is in the image rather then how it is taken. His documentary photography touches almost every aspect of life showing love, anger, grief and happiness. Throughout his work, solitude in the urban environment seems to be on of these major themes. |

| In the image on the top Cartier-Bresson went much further then just excluding the man from the outside world. The cat left as only thing to play with, makes us question the outside world. The anonymity of the city is the turf images like have been created on. Their power is their symbolic language but above all a feeling every one of us can identify with. Especially Cartier-Bresson photographing in a foreign country must have felt for this man left alone with a cat. Again, it’s not just how the image was created – the creation of the image came with the understanding of a moment. With Cartier-Bresson a new generation of photographers grew up. Image-makers who can relate to the subject, understand and interpret their needs and finally capture these truthful and without alteration. The photographers mission was to catch a glimpse of a reality so real that our fantasy couldn’t have imagined it. |

|

| Robert Frank, My Family, New York, 1951: |

| Robert Frank was working in a very similar milieu as Cartier-Bresson. His photographs were not posed and preserved moments written by life. In his book The Americans and his portfolio Black, White and Things he included at very significant parts a photograph of his family. At the beginning of the chapter called White we can see a bare breasted woman with her newborn child. Without even looking at the title of the image it is absolutely clear that the viewer is looking at the photographer wife and child. There might be many signs that make this a truly great image; his wife as Maria figure, her breast symbolizing fertility, the cats repeating the mother and child theme, the wide space suggesting a long future to come and Frank including his shadow as a indication of participation. |

| Frank is known for his ability to sequence photographs in a very sophisticated matter as we have seen in The Americans. Nonetheless, I find it very questionable if it is appropriate and important for the message to confront the viewer with photographs of the family. Not because the family shouldn’t be shown in publications - it is the singular image of privacy in a series of images taken in public that distracts me. The picture must fit the context and not the other way around. |

|

| W. Eugene Smith, from K.K.K., unknown location, 1950’s: |

| One can imagine the troubles Smith must have gone through just being able to witness one of the Klu Klux Klan’s gatherings. Taking out the camera and shoot is a whole different story. The clan members appear to be not too amused about the photographer’s presence. In fact, it looks as if his actions were just discovered in the moment Smith released the shutter. The only way I can imagine how these prints could have pass the clan’s censorship, is that Smith falsely identified himself as a partisan of the clan. |

| To shoot this assignment he put his own beliefs aside to concentrate on making images. He could still stand up for his political views, as soon the assignment was shoot. Without doing that Smith wouldn’t even be able to contact these men. In a letter to one of the members he apologizes that “it was impossible to keep [the clan members] from appearing black”. Of course this is pure sarcasm. The print was deliberately printed in that way to make the viewer realize – when put into a certain light – our skin color is not very different each other. What is described as an accident is actually a master print that created additional meaning long after the photograph was taken. |

|

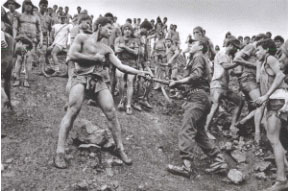

Sebastiao Salgado, Dispute among the workers of the Serra Pelada gold mine and a member of the military police from the state of Para, Brazil, 1986: |

| Salgado is one of the most respected contemporary photojournalists. His photographs are sold by photo agencies such as Sygma and Magnum – at the same time they are shown in galleries and museums all over the world. Salgado is walking on a thin line between reportage and fine art. One of the reasons Salgado’s work is so widely respected is that one can read into his pictures and get a grasp of the politics presented. The photographer himself must understand the politics involved in order to create symbolism and meaning. Salgado’s Masters Degree in economics maybe wasn’t necessary to photograph this incident in a Brazilian gold mine. But it required research, knowledge on the political situation and passion for the subject to capture what Salgado did. |

| The passionate eye is a very strong motivation one can literally see in his work. One can see in this particular example with which side Salgado is identifying with. Far beyond the very obvious body language, the viewer can find very subtle details in this photograph: the leg muscles these men have developed, their shoes compared to the ones of the police man, and how the bystanders try to remain in safe distance to the dispute without missing anything from the action. These are details that are thought of in the process of photographing, printing and latest editing. All of which Salgado has masters – the proof are images likes this. |

|

| Don McCullin, A cholera victim, Bangladesh, 1971: |

| McCullin’s photograph of a dead cholera victim assumingly carried away by her husband is one that I would like to discus as an anti-example. I acknowledge McCullin for his reportages from all over the world and – similar to Salgado – the dedication he shows for his subject. Nonetheless, on an artistic level his photographs don’t have too much in common with Salgado’s sophistication for the medium. McCullin’s photographs are very frontal, direct and ‘in your face’ referring to how and what he photographs. McCullin’s images seem to exploit the people’s intimacy by making it hard to tell if he is an observer or voyeur. Salgado makes himself transparent as a photographer by letting the photographed incident to remain as the center of attention - rather than his camera. |

| Photographs such as A cholera victim lack that transparency and therefore take away from the actual situation. This a characteristic I could find in most of his work, which also prevents it from going into deeper psychological levels of seeing. What is in itself a very powerful scene becomes just another photograph of desperation. The viewer gets numb by seeing photographs like this over and over. McCullin photographs from Bangladesh also have something else in common: the subject is usually in the center of the frame and there are bystanders in the background looking from the opposite side at the same situation then we do. In a way, McCullin - accidentally or not - lines us up with all these people watching just for the sake of watching. This aspect makes me feel as if I am seeing something I shouldn’t have. McCullin has failed to show a talent in presenting a scene of horrifying intent without taking one of the last things these people have – their image. |

|

| Martin Parr, from Common Sense, unknown location, 1990’s: |

| Martin Parr’s approach is highly unusual especially for photojournalists. In his book Common Sense he photographed with a macro lens using most of the time a ring flash. He also used a special kind of film which makes the colors of his photographs very saturated, even exaggerated. The subjects are as much exaggerated than anything else in Martin Parr’s photography. He is taking photographs on topics such as tourism, food, clothing and consuming. He compiled a photographic sketchbook of his perception on the industrialized world. After viewing his book one might have a certain disgust of the human being. There is also a great amount of humor Parr applied to his personal perception. In photographs like the one on the top the viewer might question the content, at the same time he can relate to it because we are typically dealing with everyday objects. |

| One possible version could be that a hospital patient is waiting for her partner to share the ice cream wit her. Whatever it is, Parr captures these humorous things he finds but also gives a weird undertone to it. The viewer is constantly drawn between the views of a man who practices serious criticism on culture and in contrast to that confessed his love for kitsch. This is of course highly subjective. But Parr doesn’t claim to be objective with his photography. He even admits that he arranges subjects within the frame and influences their behavior in front of the camera. This is for me more objective than anyone who claims to produce objective photographs but after all looks at society from a very particular point of view. A self-conscious subjectivity might bring us closer to truthful photographs by introducing them as what they really are – a very personal perception of our world. |

|

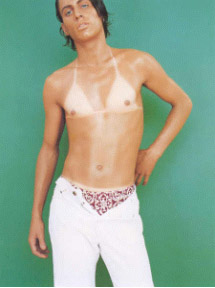

| Jean-Baptiste Mondino, World in Lotion, unknown location, 1990’s: |

| Widely acknowledged as a leading fashion photographer, Mondino goes beyond what the industry always seems to have lacked: deeper meaning. His photograph of a terribly good-looking young man is selling a pair of boxer shorts or pants. At the same time Mondino is mocking clichés people have on the fashion industry by including these bikini marks. Mondino is referring to the seventies were this was understood as being trendy. He is making a comment on past fashion trends but also on our perception of sexuality. |

| The man’s eyes, mouth, hair, skin and way of positioning himself make him look very feminine. The photograph is tricking the (male) viewer who might be attracted to the person. At second sight one realizes that this attraction is going towards a man and not a woman as first expected. In a milieu, which is over crowded by sex symbols, Mondino shows that in his understanding they can be both, female as well male. By photographing this man like he did, Mondino is questioning not only the values of the sex symbol but also the industry, which has created these. |

|

| Corinne Day, from Diary, unknown location, 1990’s: |

| With people like Corinne Day there is e new bread establishing itself in photography. She is also one of the most recent discovered talents in the field. Her first published work was on her friend Kate Moss for Vogue. Day introduced the so-called ‘grunge style’ that has been widely practiced in fashion photography throughout the nineties. With her first book – bluntly called Diary – she goes into similar directions of grunge but with an overwhelming amount of realism included. As the title suggests, the book is a photographic diary, mostly covering the story of her friend Tara who is a notorious drug addict. Throughout the book there are photographs of violence, sex, drugs and unfulfilled dreams. The viewer is reminded by the work of Nan Goldin and Larry Clark. It is that same kind of shocking realism which connects these works. |

| Nevertheless, Day’s work has been harshly attacked. Critics say that Goldin and Clark lived that realism, whereas Day just visited the realism when she wished to. She was a guest unlike Clark who was just as much a junkie as his friends he photographed. Although critics say that Day is lacking integrity I feel that there is a strong relationship between the photographer and her subjects. The viewer is able to see how Day’s friend Tara trusts her, how much she is sharing with her and how unimportant the camera becomes in these kinds of situations. Situations like the one shown in the picture above. The cocaine on Tara’s and her boyfriends nose foreshadow whatever there is to come – a never-ending cycle of excesses, narcotics and illusions interrupted by little sparks of humanity. Day was able to capture both, and was successful in presenting ten years of her friends’ life, without turning them into monsters although she had all the material to do that. |

Marco Bohr, April 2001 |

back to homepage |

|

| |

|